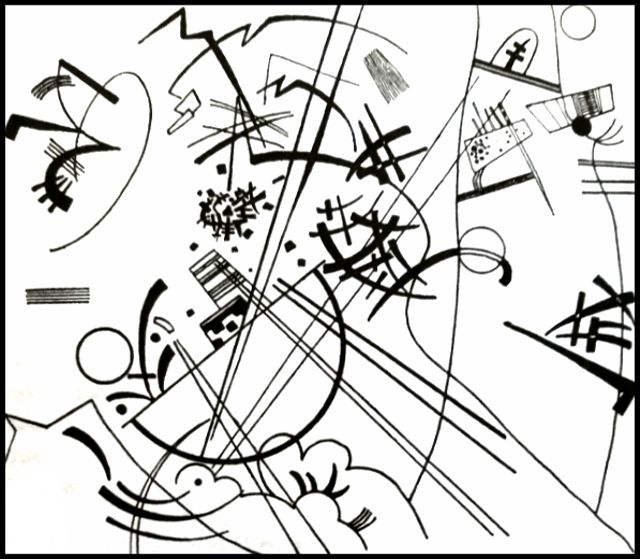

Sensory Experience of Perception

Paris and worn out shoes, German Expressionist Painters, Kandinsky

I travelled to Paris in 1984, on my first trip to Europe, to present a paper at an international symposium on urbanism.

My plane landed at dawn. After clearing customs, I took a train of the RER, the light railway system for Paris, to the neighborhood where I would be staying.

I asked several individuals for directions to rue Joseph Barra. Nobody knew where it was, but they taught me to pronounce the street name correctly.

The children of the family with whom I was staying found me. They guided me to their apartment, and after a brief visit, I washed my face and I went out to look at Paris. I walked to the Seine. Tears ran down my cheeks as I stood there with mental images of the Montgolfier brothers’ balloon drifting across the October morning sky.

During the week of the conference, I spent most of my free time wearing holes in the soles of my shoes as I walked around in the Left Bank neighborhood of my hosts.

German Expressionist Painters

Paris was not the center of Modern Art between the last decade of the 19th Century and the end of the First World War.

I graduated from Berkeley in 1968. I believed Paris to be the center of it all. I did not have a clue about the twenty years or so when the European art world included almost everyone.

If I had I read Peter Selz’s German Expressionist Painting, in 1963 instead of in 2023, I would have learned that the two decades between 1890 and the end of World War I was a time of extensive interaction and collaboration among artists from throughout Europe and beyond, with numerous exhibits showing their work. The catalog of one of those shows, the international exhibition of the Sonderbund, in Cologne, 1912, prompted the Armory Show, in New York in 1913, which introduced America to modern art.

When the war ended, the USSR supported modern art until 1934, when the party line switched from Modernism to Socialist Realism. In Germany, Expressionism gained popular acceptance as it lost its revolutionary edge. In 1937 the Nazis replaced Expressionism with kitsch artwork. Expressionists continued to work, but many joined the growing exodus from central Europe occurring toward the end of the 1930’s.