Sensory Experience of Perception

IDEAS:

In Walter Benjamin: an Introduction to His Work and Thoughts (2004 in German, 2010 in English), Uwe Steiner describes Benjamin’s discussion of Critique of Pure Reason, in which Benjamin quotes Kant to the effect, “ ... ‘that all speculative knowledge is limited to objects of experience,’ and that we can have knowledge of things only insofar as they present themselves as objects of sensory perception, that is, as tangible phenomena.”

Addressing Modernism

We are participant observers in the ongoing modernization, or globalization, of world culture.

Modernism sometimes refers to an artistic style or movement that began in Europe roughly in the last third of the 19th century and continues to the present. (Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art. Alfred Leslie’s film The Cedar Bar.)

Modernism also refers to the period of world history (and of art history) from the late Middle Ages to the present. At the beginning of this epoch the purpose of art ceased to be to depict religious themes under the patronage of the church and aristocracy and became the arena of artists and their patrons. Hans Belting wrote about this major point of inflection in Hieronymus Bosch: Garden of Earthly Delights.

“Modernism and postmodernism are not chronological eras, but political positions in the century-long struggle between art and technology.” (The Dialecticss of Seeing. Susan Buck-Morss, p.359)

The above clusters of ideas and history have a bearing on the practice and understanding of art. I hope it is clear from the sense of the text which Modernism I am writing about.

Modernism makes consideration of the formal aspects of composition necessary for the aesthetic appreciation of works of art.

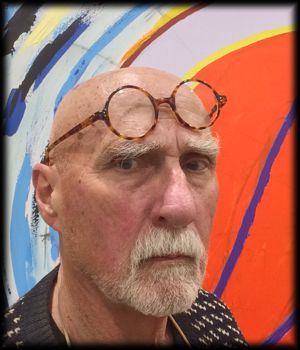

The painting to the right is one of many I have made based on a motif of rectilinear bands of color. Its success depends on the degree to which I was able to harmonize the colors and proportions of the forms.

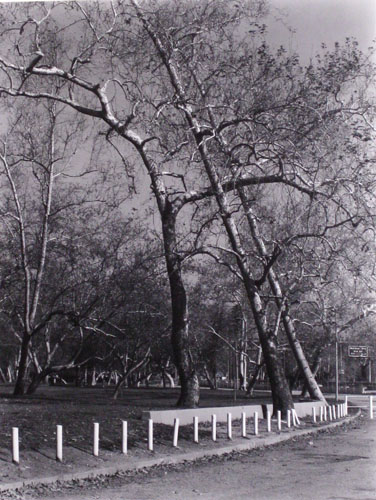

Abstract Expressionist Photograph by Aaron Suskind.

The compositional principles that apply to painting, also apply to photography.

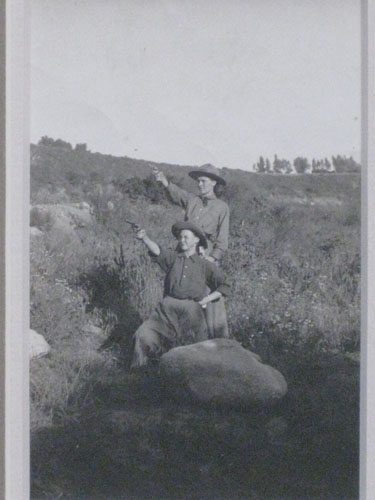

The two images below are similar in composition. However you respond to their content, or whatever meaning you might might infer them to possess, their success as works of art depends on the effectiveness, in each image, of line, form, color, and composition, in eliciting a positive aesthetic response from the viewer.